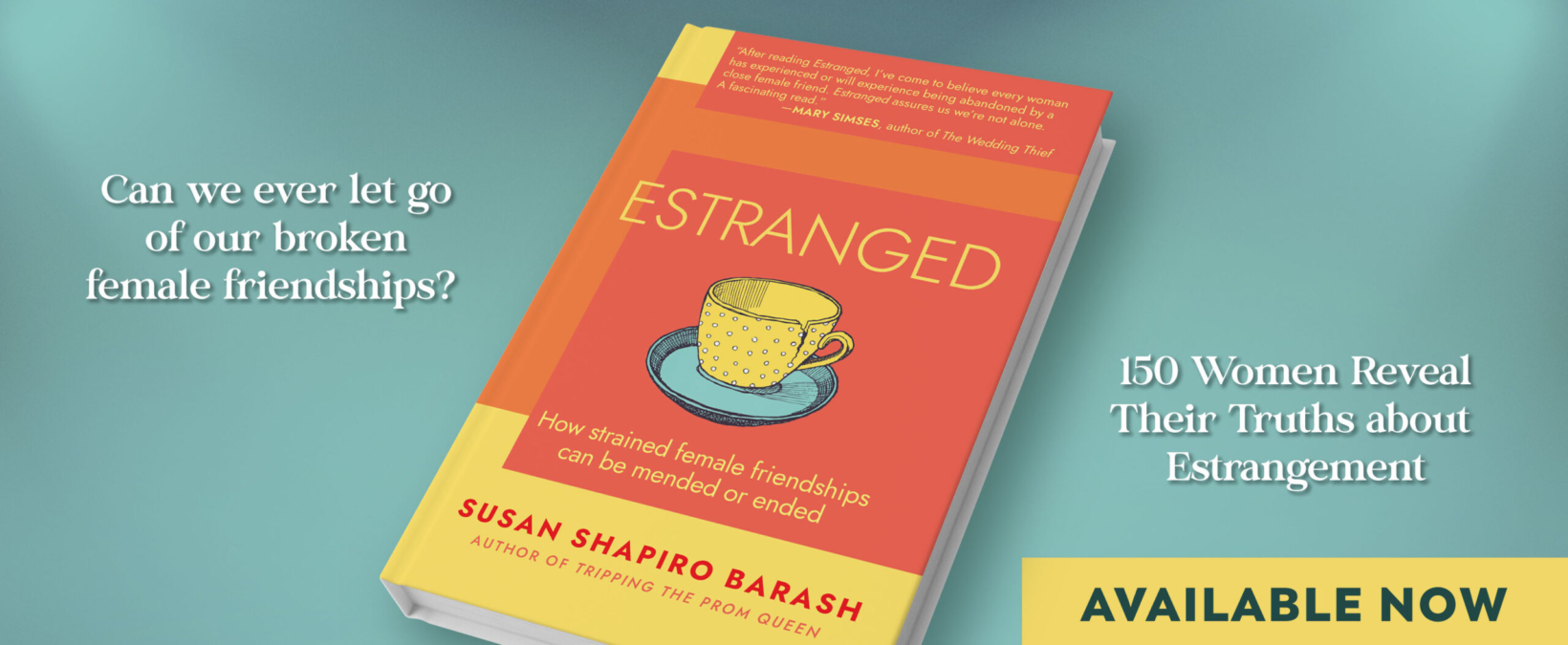

Preface for The New Wife: The Evolving Role of the American Wife

Preface for The New Wife: The Evolving Role of the American Wife

1955

“I never imagined not being married, not being someone’s wife,” begins Alice, sixty-six. “I was married at twenty-one and at that point, I imagined that my life was beginning. Finally, I had arrived. I concentrated on decorating the house and getting repairmen to fix broken dryers and ovens, sometimes the tv antennae. It was a sign of status to live in a home with wall-to-wall carpet, so we had that. I churned out three children quickly, because that is what wives did. I made innumerable meatloaves and carpooled for miles on end. And while I wasn’t unhappy, I wasn’t happy exactly. My husband was the provider so he was the boss. Being a wife gave me respect. It didn’t dawn on me for years that I could be something other than a wife. This is how I was raised.”

l965

“I was raised to think that marriage was the goal, but by the time I reached a marriageable age, the feminist movement was beginning,” Leeanne, fifty-eight, tells us.” I looked at my mother with great skepticism. I wasn’t going to toss away my college degree to be someone’s wife. The pressure from my family was enormous, and by the time I was twenty-four in l968, I caved in and I got married. Then the struggle began once I had kids—the feminist teachings confused me, because I couldn’t keep it up. Whatever I had learned about being on my own seemed to vanish. In the end, I worked with my husband to have a flexible schedule for the children. It wasn’t a compromise, it was a sellout; I had one foot in the past and one foot in the future—where wives had children and worked.”

l977

“In l972, when I graduated college, I believed that I could be anything I wanted, even as a minority woman,” Grace, fifty-two, recalls. “I won a scholarship to college and law school. I knew I wanted to marry and have a family. I thought that my husband would be understanding and fair. I imagined that we would be equals and that my career would be as important as his. I became a wife at twenty-nine and I waited until I was thirty-nine to have a child. By then I had to have infertility treatments. I was proud of my success as a lawyer, but disappointed in my marriage. I fought with my husband, looking for the romance we’d lost and somehow blaming him. When my daughter was born, I fell in love with motherhood because it had been a struggle to get there. Then my husband had an affair and I became very tired. I couldn’t be a wife/mother/lawyer and hold it all together anymore. I encourage my daughter to make her own money and to expect little from marriage.”

l984

“The road was paved for me by my predecessors,” Karine, forty-six, explains. “Those women who had achieved success and also married and had children were my role models. I didn’t believe in the downside of being a wife, I believed in romance and everlasting love. I got married at thirty-three, and kept going in my career as a stockbroker. It took me a long time to realize that women still were not treated well in the workplace and my inner voice wondered what it would be like to be a wife and mother, only that. Eight years ago, my husband and I adopted a daughter from Korea and I took time off. But I couldn’t be just a housewife, so I became a powerful wife and marked my place in our community. I invested my brainpower into my job as a wife and my husband benefited from my social skills. I often wonder what is ahead for my daughter.”

l993

“I was a catch of a wife when I married my husband in l990,” Carly, thirty-nine, remembers. “I had gone to the right schools and I was open to working or not working. I looked at my sister who was ten years older and she was already contemplating divorce. Our mother had been stuck in a lousy marriage. I wanted to avoid that route so I decided to focus on the marriage although I was overqualified to run a house. I opened a home office so I could keep up the house and the girls, and for a while it was enough, although I found it very lonely. I felt like life was passing me by—I was arm candy for my husband. In the late nineties I began to wonder what more there was out there and how many good years I had left, for work, to look good, to be a riveting wife. I had an affair with my plumber, and during that time I felt I was an extraordinary wife—I couldn’t have been more glowing in my deception. The truth was, the constraints were too much, despite my efforts to be a perfect wife.”

2002

“If I didn’t marry early I would fall into the same trap as my mother,” explains Deirdre, thirty. “She is divorced and has not gotten what she wanted because she tried too hard. I want to be young when I have children. I am determined to work on my marriage and to be a team with my husband. I don’t want to be considered a ‘wife’ as much as a partner. It matters to me that we started out early. I can be anything I want to be, and I want to be Jeff’s wife. I want to be a happier wife than my mother has been. I don’t want to pretend things are okay like my grandmother did. I want to avoid these traps.”

It is an intriguing notion that a woman’s identity today remains wrapped up in the role of wife. Yet, the attitudes and expectations of this role have evolved so that a woman who becomes a wife today is not positioned in the same way as a woman who became a wife as recently as ten, twenty or thirty years ago. Although being a wife is as desired now as it has been in the past, the point of view of the wife is altered. A young wife today believes that her marriage will be egalitarian; filled with options and without complacency. Her marriage is also partly reminiscent of the past, partly unprecedented, partly a reaction to AIDS, her parents’ divorce and life after 9/11. Whatever modeling she has found in her mother, she is determined to have a different experience than a wife of thirty years ago.

The new wife’s sense of entitlement and power is more pronounced than that of her predecessors. This is not to say that her predecessors have not adapted to degrees. There is little question that a woman who became a wife twenty-five years ago has changed with the times, and these changes impact the young wife in much the same way as do traditional precepts of marriage. The original concepts of a wife of the past fifty years—status, companionship, family, and protection, are still valid. Yet, the balance has changed. The revised imprimatur, but an imprimatur nonetheless, of being a wife, holds fast. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the paradigm of wife is being redefined.

It matters little to women that over the course of centuries, wives have simultaneously suffered physical beatings and commanded respect by reasons of their status. Despite an undercurrent of disparagement, including jokes, coffee klatch complaints, the commiseration of women at health clubs and at the office, women yearn to be wives. Young girls dream of it, divorced women and widows search for another chance, and single women view themselves as less, as missing something, because they are not wives. What was held up to us in the l950s—a wife who cherished her duties at home and seemed devoid of intellectual challenges—is a stereotype long gone. A wife today does not perceive herself as a prisoner in the home, nor a mother, nor a feminist, nor an antifeminist. She is aware of the complexities of her role, and within her own tenure as wife she will change her style, she will adapt to a current trend or she will buck it. Whatever path a wife chooses, be it a power wife, arm candy for her husband, a stay-at-home wife, or a career wife, being a wife is still considered a definition of self and representative of one’s acceptance in the world. Whether a woman is a wife or not, she lives in a society that considers it both an achievement and a compromise. What she imagines her role to be is represented by her mother and stamped with her own twist. The complexity of the mother-daughter role reveals daughters who repeat their mother’s patterns of being a wife, choose an opposite style or a portion of their mother’s style, combined with up to date mores and expectations.

As a two-time wife, and having spent my adult life at it—sixteen years in my first marriage and six in my second—I recognize the obstacles and the perks of the position. I have listened to the longings of my friends and I have eavesdropped on unknown women lamenting their fate as single women, perplexed wives, and triumphant wives. As an author who documents the lives of women, I have interviewed those who have conducted extramarital affairs, those who have divorced only to remarry the same type of man, women who have resented the husband’s ex-wives, and women who “sleepwalk” through their marriages. In any of these scenarios, the concept of being or not being a wife is at the heart of the matter and remains a defining aspect of a woman’s life.

Everlasting love and marriage are encouraged by our culture. Media, film, theater and literature, each use the theme repeatedly, occasionally with a twist. If we flip through the pages of People magazine, we are brought up-to-date on who becomes whose wife and who divorces whom, losing wifely status in the process. Recently, many wives have sympathized with Nicole Kidman, who, according to the press, was relieved of her wifely duties by her then husband, Tom Cruise. It was big news when actress Julia Roberts embarked upon her second chance at being a wife. On July 4, 2002, she and beau, Danny Moder, exchanged vows at Roberts’ ranch in Taos, New Mexico. The same day Candace Bushnell, creator of Sex and the City, and Charles Askegard, a ballet dancer, were married on a beach in Nantucket. In both cases the press noted that the wives are older than their husbands, Roberts by one year and Bushnell by ten years. While neither wedding was conventional in terms of style, becoming a wife is time honored and prescriptive. One of the more surprising marriages is that of Gloria Steinem, renowned feminist, who at the age of sixty-six married sixty-one-year-old David Bale in 2001. According to those close to Steinem, her role as wife is exciting and rewarding.

When we think of the complicity of wives, there is Lady Macbeth, who might have washed her hands of evil deeds but was the one who had the power, good or bad, to encourage her husband all along. One of the more tenacious wives throughout history is Anne Boleyn, who convinced King Henry VIII to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and marry her. This action on the king’s part established the Church of England and allowed divorce. Anne Boleyn’s marriage to the king forever sealed the fate of the wife, allowing divorce to enter the equation, so that women are free to leave a disappointing marriage and allowing their husbands the same advantage. Any woman, in fact, is able to jockey for the position of wife and she may choose to go after a married man, rather than a single man. However, this does not guarantee that a wife will be happy with her lot once she achieves it, or that she is content with her role. Current fiction, film and television series emphasize the unmarried female, characters that yearn for the right mate yet would not necessarily be able to recognize him upon arrival. This present-day barometer of women and wives points to the fact that while many paths are available to women, marriage, for women under the age of sixty-five, remains the most glorified and sought after of them all.

Each decade since the end of World War ll has altered the face of marriage to varying degrees and in the process has transformed women’s lives. Portions of the original wife have remained—those of committing to one man on many levels for a lifetime, the idea of raising a family together, the recognized unit of husband and wife. While every ten years has produced major changes in the role of the wife, what prevails is a new version of the wife.